A Nation of Steel:

The Making of Modern America, 1865-1925

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995

Chapter 1: THE DOMINANCE OF RAILS (1865-1885)

![[A Nation of Steel]](../images/NOS-thumb.gif)

| Thomas J. Misa

A Nation of Steel: The Making of Modern America, 1865-1925 Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995 |

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1: THE DOMINANCE OF RAILS (1865-1885) |

![[A Nation of Steel]](../images/NOS-thumb.gif) |

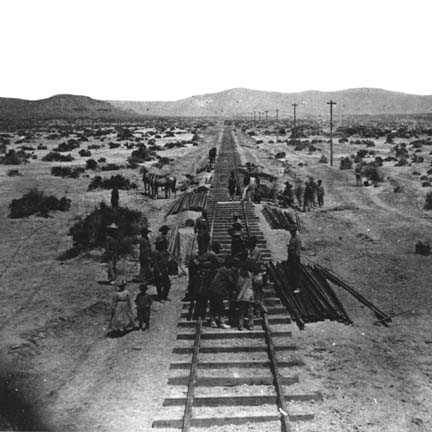

No grading bottleneck faced the Central Pacific; nor did it plan a marathon. "We must organize," Crocker had directed James Strobridge, who had pushed the track-laying crews at breakneck pace for months. "You don't suppose we are going to put two or three thousand men on that track and let them do just as they please?"2 In sending the entire railroad car-by-car across the Sierra Nevadas, the Central Pacific's supply staff had developed an exquisite system that loaded 16 flatcars with every item needed for two miles of track. Five such trains were moved to the front, positioned on the main line or convenient sidings. Ties had already been distributed along the graded path. A crack team of 850 track layers, enticed by the challenge and by the prospect of quadruple wages, stood ready. A locomotive derailment had halted the try the day before, but now all was ready again.

At 7 a.m. Crocker raised his hand, the locomotive of the lead supply train blasted its whistle, and the Central Pacific's machine made of men swung into action. Chinese laborers began unloading the first train: kegs of spikes and bolts, bundles of fish-plate fasteners, rails. "In eight minutes, the sixteen cars were cleared, with a noise like the bombardment of an army," wrote one correspondent.3 As soon as the supply train was out of the way, six-man gangs lifted onto the track the "iron cars," small flatcars fitted with rollers to speed the on-and-off movement of rails, and began loading each with sixteen rails plus necessary hardware. Two horses pulled each iron car to end of track, where they were unloaded by Chinese. Meanwhile, a three-man team with shovels had gone ahead to align the ties with the surveyor's stakes at track center.

At end of track stood the eight strapping Irishmen with tongs to grab the rails. A portable track gauge-a wood-framed device that ensured 4 feet 8 1/2 inches separated each new rail pair-was moved ahead by two additional men. The Irishmen worked two men at the head and tail of each rail, on both sides of the iron car. As the forward pair seized each 30-foot rail, the rearward pair helped guide it over the rollers and onto the cross tie. As soon as the rail was in place, one gang started the spikes, eight to each rail, and bolted fishplates at each rail joint; another gang finished the spiking and tightened the bolts. As end of track moved forward, ten yards at a clip, track levellers followed in its wake, lifting ties and shoveling dirt under them as needed. At the rear of the column, which eventually stretched out some two miles, were 400 tampers, with shovels and iron bars to give the road bed a firm set. Whenever a workman tired or faltered, a fresh replacement took his place.

Progress that day was phenomenal. The Union Pacific's observers timed the column proceeding down the tracks at 144 feet per minute, a pair of rails every twelve seconds. Another observer witnessed 240 feet of rail laid in a minute and twenty seconds. At a pace that one might average on a day's walk, the Iron Horse was moving across the desert. "I never saw such organization," marvelled an Army officer. "It was just like an army marching over the ground and leaving a track built behind them."4

At 1:30 Crocker gave the signal for an hour's lunch break. James Campbell, superintendent of the division, ran the camp train in and served 5,000 dinners to workers and guests. "That morning," recalled Strobridge, the construction superintendent, "we laid six miles in six hours and fifteen minutes, and although we changed horses every two hours, we were laying up a sixty-foot grade, our horses tired and could not run."5 After an hour's rest the crews returned to action. For almost an hour the most important task, conducted with hammer, wood blocks, and eyesight, was bending rails for the upcoming curve. As the shadows lengthened, the last supply car was unloaded, then the final few iron cars. By seven in the evening, the ten miles of new track, plus 56 extra feet, was complete. The effort had consumed 25,800 ties, 28,160 spikes, 14,080 bolts, and 3,524 rails. But the most prodigious feat of the day was that of the eight Irishmen, who waved off the replacement crew offered them at lunch and stuck out the entire grueling day. Each four-man team hefted nearly 1,800 rails, every one at 56 pounds per yard and 30 feet weighing 560 pounds; together, the eight men handled that day just over 2 million pounds of rails.

The eight heros' mark was never broken by the Union Pacific, and the restless tempo of railroad building soon yielded to the irresistible press of running the railroad. In just 40 minutes superintendent Campbell ran an engine over the new ten-mile track to prove its soundness. Within two days, at a more leisurely pace, the two rival crews laid the last rails that took their ends of track to Promontory Point, Utah-690 miles from Sacramento and 1,086 miles from the Missouri River-and waited for the big-wigs to arrive. There, on May 10, as Maury Klein relates it, "the wrong people came to the wrong place for the wrong reason."6 Absent from the ceremony were the most important promoters of each railroad, who were in New York or California on business. Nor was there any government representative for this most impressive of the nation's internal improvements. Neither of the railroads had wanted to meet there; both hoped to build more mileage and thereby claim more construction bonds. Only a Congressional resolution in early April designating the point of junction prevented an open feud. After the Central Pacific's Leland Stanford and the Union Pacific's Thomas Durant both took awkward swipes at the Golden Spike, missing it entirely and instead squarely whacking the rail, the telegraph message went out to the world: "THE LAST RAIL IS LAID! THE LAST SPIKE IS DRIVEN! THE PACIFIC RAILROAD IS COMPLETED!"

If less easily cast in a heroic mold, the machine made of iron that lay behind the transcontinental railroad was no less impressive. That year, 1869, the nation had never before laid so many miles of rails, nearly 5,000. Imports, previously a dominant source of rails, were held down by the domestic-only provision of the Pacific railroad legislation. Indeed, domestic rail production had grown handsomely with the expansion of Pennsylvania's iron industry and with rail re-rolling operations scattered from Worcester to Chicago. Output of new rails began climbing impressively after 1857 when John Fritz's three-high rail mill cut the amount of arm-busting labor needed to form square bars of iron into finished rails with their distinctive inverted T shape. As mills adopted Fritz's invention the tally of rails climbed ever higher. From 1855 to 1865, scarcely dented by the Civil War, rail production increased 250 percent.

Yet, however much labor had been saved in the rolling mill, still more back-breaking labor was necessary before the iron was suitable for rolling in the first place. For each of those rails had begun life in the blast furnace as a mixture of limestone, coal, and iron ore that was melted down-smelted-into crude iron and waste slag. Iron directly from the blast furnace, known as pig iron, was a brittle product suitable for casting into pots, stove plates, and the like, but totally unsuitable for rolling into rails or anything else. Refining of the crude pig iron was accomplished by a skilled workman at a puddling or boiling furnace. There a half day of careful stirring and heavy manipulation yielded a large ball of pasty and fibrous iron, which was hammered or rolled into "wrought iron" bars that could be sent to the rolling mills. The rub was that expanding the output of wrought iron required additional skilled workers; capital for production equipment alone was insufficient. The most important workers were the skilled puddlers, an independent lot, the "aristocrats" of the industry. Inevitably, puddlers organized the early iron unions, with a propensity for effective strikes. A strike at the Cambria mill in 1867 briefly stalled the Union Pacific in its march across the continent.8

By the early 1870s, with railroad construction at fever pitch, there emerged tell-tale signs of an industrial system pressed beyond its limits. The price for iron rails jumped $15 a ton, to $85; steel rails went to $120 a ton. Even if the land-grant railroads were limited to domestic rails, their competitors were not. From 1867 to 1872, increased demand for rails was met mostly by increased imports; domestic iron production had stagnated. In 1872 more steel rails were imported than were produced in America; together iron and steel imports constituted a third of the 6,000 miles of track laid that year.9 These figures raised the nagging question of who, or what, could fill the yawning gap between domestic production and domestic consumption? If ever there was fertile ground for a process to mass produce steel for rails, it was the United States in these years of extensive railroad building. Like most of those steel rails, the process that filled this gap was imported from England and transformed by a new geographical and economic context. In overall scope and detail, the new process would afford evidence of the dominance of rails.

1. John Hoyt Williams, A Great and Shining Road: The Epic Story of the Transcontinental Railroad (New York: Times Books, 1988), 234, 260-63; Maury Klein, Union Pacific: Birth of a Railroad, 1862-1893 (Garden City: Doubleday, 1987), 218-19.

2. Wesley S. Griswold, A Work of Giants: Building the First Transcontinental Railroad (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1962), 307-12, esp. 308.

3. Griswold, A Work of Giants, 309.

4. James McCague, Moguls and Iron Men: The Story of the First Transcontinental Railroad (New York: Harper & Row, 1964), 304-8, esp. 306; Williams, A Great and Shining Road, 262-63; Griswold, A Work of Giants, 311.

5. Edwin L. Sabin, Building the Pacific Railway (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1919), 200-4.

6. Klein, Union Pacific: Birth of a Railroad, 220-28.

7.

On Fritz, see Lance E. Metz and Donald Sayenga, “The Role of John Fritz

in the Development of the Three-High Rail Mill 1855-1863,” paper to the

1990 Society for Industrial Archeology conference, Quebec.

8.

Klein, Union Pacific: Birth of a Railroad, 137. For the labor-intensive

manufacture of wrought iron, see "ch2: groundwork" as well as John N. Ingham,

Making

Iron and Steel: Independent Mills in Pittsburgh, 1820-1920 (Columbus:

Ohio State University, 1991), 34-36; and David Montgomery, The Fall

of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism,

1865-1925 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 14-17.

9.

Only part of the imports can be traced to a revision in the tariffs on

steel rails: in 1870 tariffs stood at a punishing 45 percent ad valorem,

around $48 per ton; in 1871 it was eased to a flat fee of $28 per ton.

Imports vanished after 1874 on sharply falling domestic demand; see Figure

I.6.

Copyright 1995 The Johns Hopkins University Press. All rights reserved.